In Germany, when you talk about sports in the sense of doing more of it, you will almost inevitably come across the following expression:

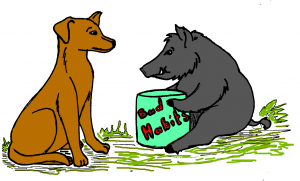

seinen inneren Schweinehund überwinden (literally: to overcome your inner swinehound)

Meaning: to make yourself do something that you really don’t want to do

“Swinehound” was the collective term for dogs which were specifically used in boar hunts because of their particular resilience and tenacity. They packed the boar and held on to it to slow it down or hold it in place until the hunters arrived. The idiom points to this tenacity: The “inner swinehound” stands for your bad habits, which are as difficult to break as it is for a boar to escape. The idiom is generally used in connection with doing things that would be better for you (as it would be better for the boar to free itself from the hounds…). As such it always implies the need for more self-discipline.

The most fitting English translation would be:

to overcome/beat/conquer your weaker self

as it conveys the same need for self-discipline.

The common translation “fighting your inner demons” goes into a different direction as inner demons are associated with dark or negative emotions or memories, not bad habits.

I have also seen it translated as “overcoming/resisting your inner temptations,” but this is a rather awkward construction. For one, temptation itself is already an inner urge or desire, so the adjective “inner” seems superfluous. Also, the expression only works if you qualify what the temptation actually is. So yes, you could say, “I have to resist the temptation of being lazy/ eating chocolate” which also conveys the need of being more self-disciplined, but the German idiom does not require this kind of qualification. (Eine deutsche Erörterung des Themas befindet sich hier)

(Eine deutsche Erörterung des Themas befindet sich hier)

(Quelle: Minard, Antone. Western Folklore, Vol. 69, No. 1, Winter 2010, zu finden

(Quelle: Minard, Antone. Western Folklore, Vol. 69, No. 1, Winter 2010, zu finden  (You’ll find an English discussion of this topic

(You’ll find an English discussion of this topic